On a terrace stands a five-year-old girl in the twilight. It is late summer and it is almost bedtime for small children. T he night lights get turned on one by one in the nurseries in the houses on the suburban street just outside Copenhagen. But the girl will not go inside. She wishes her mother would be able to tuck her in.On a terrace stands a five-year-old girl in the twilight. It is late summer and it is almost bedtime for small children. The night lights get turned on one by one in the nurseries in the houses on the suburban street just outside Copenhagen. But the girl will not go inside. She wishes her mother would be able to tuck her in. She looks after mother, who pedals her bike in the direction of the Royal Theatre, the Danish national scene. She has to get on the stage soon. She is employed in the opera choir, and when she rides back to her family in Søborg around midnight, the applause and the echoes of the singing will still resonating in her ears.

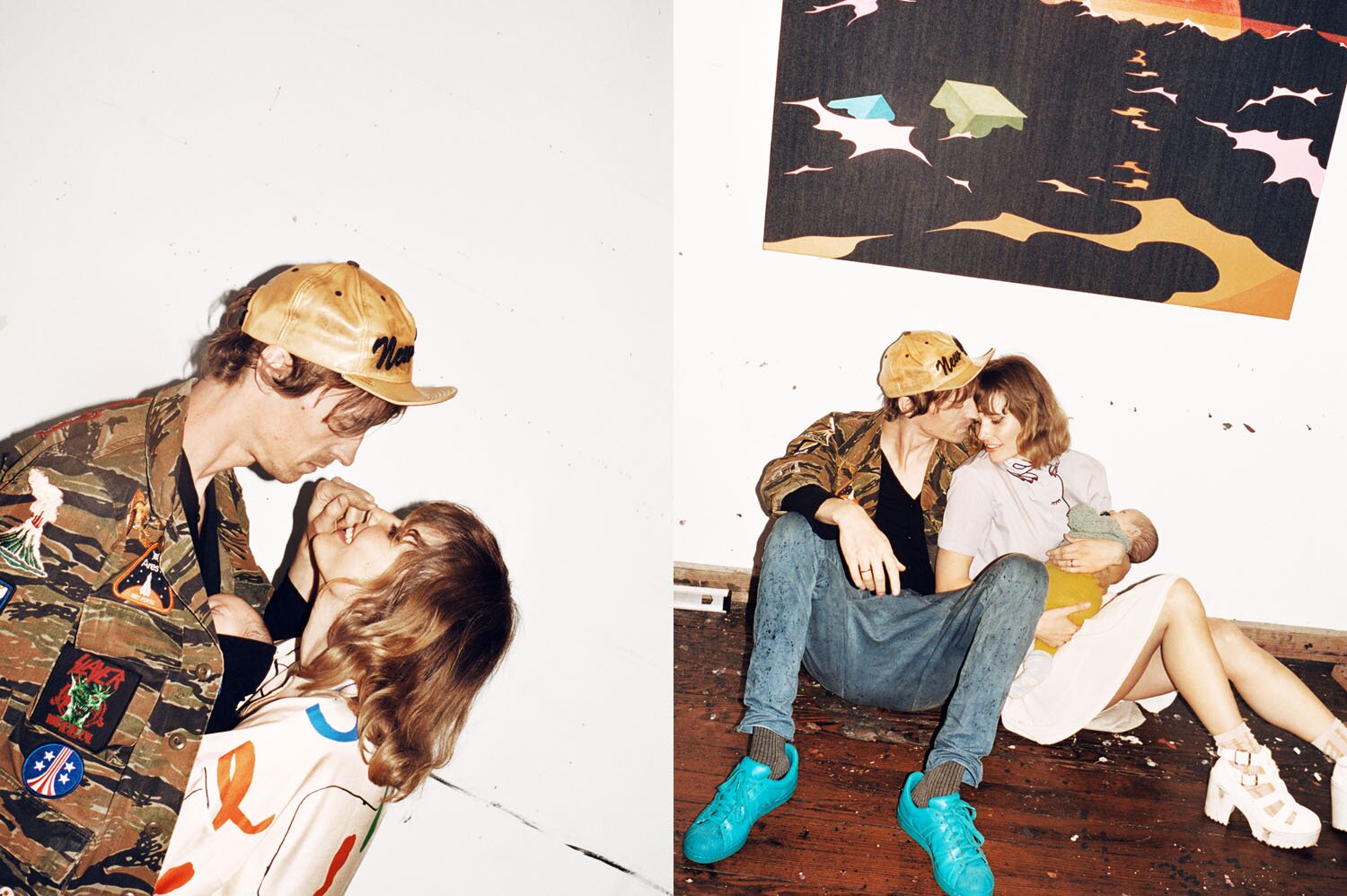

“Very early in my life I understood that the theatre sometimes was a bigger thing than my childlike needs. I’ve always respected that when you went on stage, that was it, that was the main thing right then. And then I had to be quiet.” The words are spoken by Nanna Øland Fabricius – better known in the wider world as pop singer Oh Land. As a child of creative parents she has become intimately acquainted with that space in which you are deeply immersed in the articulation of creativity. The space in which you are alone with your passion. “Since I was quite young I’ve had great respect for professionalism. Now I can see that it must have been super hard for my mum to leave a crying child behind. That’s definitely something I think about nowin connection with this little guy,” she says and nods toward her two- months-old baby boy, squeaking softly in her arms. He is swaddled in a blanket and does not seem to worry about anything.

Nanna Øland Fabricius’ mother sang opera at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen and her father was an organist and composer. She remembers her childhood in Søborg, which was sometimes full of fun and games and sometimes cloaked in hushed reverence when her mother had singing lessons or her father needed to rehearse before a concert. And that is how it will be with the son she now holds in her arms, she rationalizes.

“I can’t take him along every night when I have a gig to play. But my own history isn’t something that saddens me today, I have no regrets. I understood why it had to be like that, and it hasn’t been so tough on me that I haven’t become the same. I remember bringing sacrifices, I remember difficulties, but that kind of childhood can be a great gift,” she says.